Throwing Cold Water on the Northern Sea Route

by Victoria Barber, Olivia Jones, and Andrew Koch

As the winter weather begins to break on the East Coast of the United States, the ice covering the world’s newest trade “superhighway” is just reaching its peak for the season. Soon it too will begin to recede, opening up the potential for trade along the Northern Sea Route. This new highway runs across the top of the world, stretching from Northern Europe through the Kara Strait, along the shores of Russian Siberia, and into the Pacific via the Bering Strait. With the increase in global temperature over the last 100 years, the Northern Sea Route has started to become accessible for global trade during the summer months, and with that newfound accessibility, some see the route as the next great artery for world trade. According to its proponents, this passage would allow companies to cut at least 20 days off of their journeys when shipping from Asia to Europe and save upwards of 1,000 tons of fuel per trip, providing significant savings for shipping firms. However, based on our analysis, the idea of the Northern Sea Route as a transformative trade route does not pass muster. Yes, it may become a vital route for global shipping in the future, but that day is still far off.

Projections

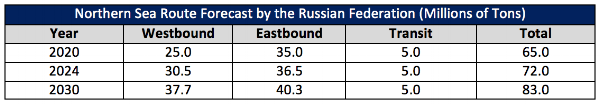

During the 2015 Arctic Circle Assembly held in Reykjavik in October, the Russian Federation’s delegation provided their projections for the future of the Northern Sea Route. These projections are summarized in the table below.

While the total numbers seem to portray increasing commercial traffic passing through the Northern Sea Route over the next 15 years, the three categories (westbound, eastbound, and transit) contain an important distinction. Westbound and eastbound traffic include routes that have either an origin in or destination at a Russian port, while transit traffic captures trade with an origin and destination in any country other than Russia (i.e. East Asia-to-Europe or Europe-to-East Asia). So in reality, the Russian Ministry of Transportation predicts a relatively small five million tons per year of East Asia-to-Europe or Europe-to-East Asia traffic by 2020, and that this number will stay constant for ten or more years. In other words, it forecasts no increase in non-Russian commercial traffic. This weighting of Northern Sea Route traffic toward Russian trade is borne out by current metrics. According to the Barents Observer, the following are the transit metrics over the last three years along the Northern Sea Route.

We can see that the transcontinental or transit trade has actually decreased significantly over the past three years, while the trade to and from Russian ports has increased substantially over the same period.

To put this in perspective, let us compare the proposed traffic for the Northern Sea Route with another of the world’s trade superhighways. The chart below shows the annual tonnage of shipping passing through the Suez Canal.

If we compare the projected numbers from the Russian Federation on the Northern Sea Route with these numbers from the Suez, we can clearly see that the Suez traffic dwarfs even the most promising projections for the Northern Sea Route. In fact, according to their estimates, the annual tonnage along the Northern Sea Route will be approximately the same as the monthly tonnage through its rival route. Thus, despite all of the hype, the Northern Sea Route looks to be more of a bit player in global trade than the giant that has been pushed by some shipping firms and the Russian government.

Russia’s Northern Renaissance?

Despite this subdued assessment, one actor ostensibly stands to gain from the Northern Sea Route’s thawing: Russia. With the increasingly balmy weather in the High North during the summer months, the number of permanent Russian ports along the Northern Sea Route may increase. As we saw from the Russian delegation’s projections for the Northern Sea Route during the 2015 Arctic Circle Assembly, they believe that by 2030 roughly 94 percent of shipping along the route will be destined for Russian ports.

Considering the data, however, their projections are wildly optimistic. The Russian estimates represent an increase of over 1,300 percent of projected cargo from 2015 to 2020. This enormous increase seems even more implausible given that Northern Sea Route traffic actually declined by two percent from 2013 to 2014, although it did grow by 15 percent the following year. Exponential growth in tonnage is constrained by a multitude of factors: effective deployment of ice breakers, congestion concerns, port infrastructure investments and project timelines, and sheer supply and demand. Do Russian port owners, shipbuilders, and regulators fully believe an increase from 4.6 million to 65 million of tonnage is realistic within a 5-year time frame? We believe they do not. So why is the Russian Federation projecting such high numbers? Some point to a security nexus between the opening of the Northern Sea Route, increased transit projections for the route, and the recent military build-up in the Arctic.

Military Dominance?

While it is true that Russia has increased the number of its military installations along the Arctic coast, which could account for some increase in Northern Sea Route traffic, our assessment is that this is more benign than escalatory. The military build-up is unsurprising given Russia’s desire to open the area to development and trade. In fact, if one were to superimpose the proposed military installations on the Siberian coast with the naval bases along America’s Gulf Coast, one would likely see many similarities in the layout and number of bases. While we are not defending Russia’s adventurism on its other borders, we do not see Russia’s military build-up on the Northern Sea Route as anything more than an effort to ensure the further development of the north. Instead, we believe that the Russian Federation’s extremely high projection for a growth rate in shipping along the Northern Sea Route is based on considerable optimism, with some measure of propaganda. In a time of weak economic growth, the prospect of a new trade superhighway, the majority of which would run along Russian coasts, is attractive. Thus it is in the government’s best interest to play up the potential as much as possible. This helps both convince the external actors that the Northern Sea Route is a new player on the global trade market and bolster the Russian regime’s trade credentials with its own people in the face of a declining economy.

It is clear from our analysis that the Northern Sea Route will not be the next superhighway for intercontinental trade. Despite some advantages in terms of shipping length and fuel savings, it is likely that other logistical costs and the limited timeframe in which shipping is possible will prevent the route from challenging other major trade arteries for the foreseeable future, as evidenced by the projected traffic. However, we should expect to see the Russian Federation continue to play up the Northern Sea Route’s potential during international conferences and trade negotiations. While the optimism from the Russian government burns hot, the ice along the Northern Sea Route once again settles in for a long winter.

Image "Russian icebreaker Vladimir Ignatyuk" Courtesy Deb Wilfong (National Science Foundation) / Public Domain

About the Authors

Victoria Barber is a second-year Master’s candidate at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

Olivia Jones is a joint degree candidate at The Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth and The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

Andrew Koch is a second-year Master’s candidate at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.